![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

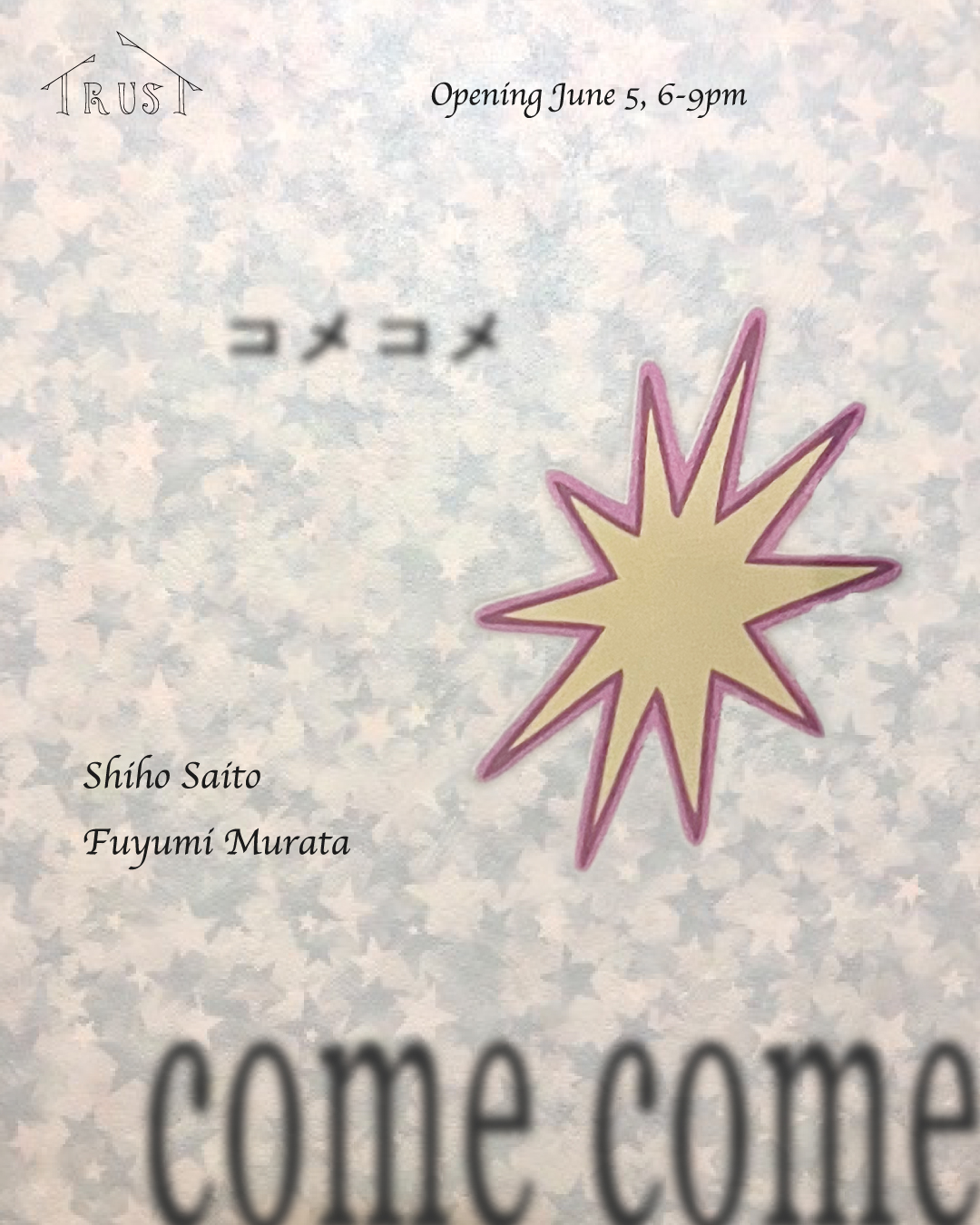

Come Come

Shiho Saito, Fuyumi Murata

斉藤思帆、村田冬実

at Trust, Vienna(オーストリア、ウィーン)

2-6pm, June 6-7, 2025

invited by imlabor with text by Reina Sugihara

Many of Shiho Saito’s works take the form of portraiture. In the early stages of her Portrait series, she depicted pop stars and other figures to whom she felt a deep personal connection, employing techniques such as printmaking and silkscreen on delicate surfaces like washi paper. Over time, however, her motifs have shifted toward found images and mannequins— that are selected simply for painting that seem to be insignificant to her. This shift signals a deeper investment in the act of painting itself that Saito is able to fully immerse herself in painting as a practice—one that exists for its own sake. Her works become quiet mediators of this process.

The figures she renders are draped in unsettling hues, unmoored from the realm of the living. Rather than portraits of specific beings, they seem to exist as images always intended for the pictorial plane—tenuously anchored to the fragile surface of paper.

Saito’s approach to installation similarly resists conventional hierarchies of display. What might be described as a “non-insistent” mode of presentation—pasting works directly onto windows or draping them loosely across shelves—suggests a sensibility of return rather than imposition. The works do not assert themselves in space so much as inhabit it, as if they have quietly come home.

In contrast to these earlier methods, the works shown in the two-person exhibition Come Come are housed inside acrylic boxes, with portraits casually affixed to wallpapered surfaces within. This format is something Saito has been exploring since 2013.

Set into small enclosures embedded within the exhibition space, the portraits appear like quiet visitors—gazing out at us from within their own contained spaces. It is as if they’ve momentarily appeared in the room, not to be displayed, but to peer back at us—or perhaps without knowing why they are here at all.

Fuyumi Murata primarily creates installation works centered around photography. In her recent Wonderland series, she prints casual, everyday snapshots taken on her iPhone, then physically tears and reconstructs them into three-dimensional forms. Also on view is Right hands, a cast of her dominant hand made in Jesmonite—a symbolic and reductive gesture that reflects her interest in the act of hanging artworks on a wall.

Presenting for the first time in this exhibition is her BAM series, based on photographs of cautionary signage found across urban Japan. In these works, exaggerated graphic elements—often added to emphasize caution or other safety measures—have been separated from the main image. Designed in the style of posters, the compositions borrow from the visual language of manga and other forms of pop culture, using simplified effects that presuppose a shared understanding between maker and viewer—one shaped through collective visual familiarity.

Underlying these forms is Murata’s ongoing exploration into the threshold between what is considered “art” and what is not. Her works consistently trace the tension between objects that are displayed, that display themselves, and that assert autonomy as artworks. What emerges is a quiet questioning of the conditions under which something begins to function as “art.”

Both Saito and Murata’s works create space for quiet attention. They do not impose meaning, but instead encourage viewers to spend time with them, gently drawing attention to what is often overlooked. Rather than telling us what to see, they invite us to slow down and notice—without urgency, without insistence.